The Great Hashrate Migration: Africa’s Pivot from Resource Export to Digital Sovereignty

Executive Summary

The global geography of Bitcoin mining—the industrial conversion of electrical energy into digital commodities—is undergoing a profound reconfiguration. Between 2021 and 2025, the African continent has emerged from the statistical margins to command a strategic foothold, estimated at between 3% and 4% of the total network hashrate. This ascent is not merely a story of technological adoption but a complex geopolitical and economic phenomenon driven by the displacement of capital from East Asia, the utilization of stranded energy assets in the Global South, and the relentless search for yield by international mining syndicates.

The epicenter of this shift is Ethiopia, which has rapidly positioned itself as a global hydro-mining heavyweight. By leveraging the colossal surplus of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), the nation has attracted over 600 MW of mining load. However, this growth is characterized by a stark and troubling dichotomy: the technical success of hashrate deployment versus the economic fragility of local value capture.

This report identifies and analyzes a critical structural flaw in the current paradigm, termed “Hashrate Exfiltration.” This mechanism describes the process whereby foreign capital utilizes African energy resources to generate digital assets that are immediately repatriated to offshore jurisdictions. While host nations receive utility payments in fiat currency, they often fail to retain the appreciating asset (Bitcoin) or the high-value industrial knowledge associated with the sector.

Conversely, a parallel narrative is emerging in East Africa, championed by entities like Gridless and the Green Africa Mining Alliance (GAMA). This “high-capture” model integrates small-scale mining with rural mini-grids, utilizing Bitcoin revenue to subsidize electrification for underserved communities. As of 2025, the sector stands at a regulatory precipice. With Ethiopia pausing new licensing and Kenya enacting the sophisticated Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASP) Act, the continent must pivot from a “resource-export” model to a “compute-integration” model to avoid replicating the extractive patterns of the past.

Part I: The Geopolitics of Hashrate and the African Pivot

To understand Africa’s current position in the Bitcoin network, one must first analyze the seismic shifts in the global mining landscape that precipitated this migration. The rise of African hashrate is a downstream consequence of policy decisions made in Beijing and Washington, creating a hydraulic pressure that forced capital into the continent’s energy markets.

1.1 The Great Migration: Post-China Dynamics (2021–2023)

For the first decade of Bitcoin’s existence, the “center of gravity” for network security resided firmly in the hydroelectric provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan, China. Controlling the majority of global hashrate, Chinese miners benefitted from symbiotic relationships with local grid operators. This hegemony collapsed in May 2021 when the State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued a sweeping ban on cryptocurrency mining, citing financial risk and energy targets.

The immediate aftermath was an exodus of industrial scale. While North American publicly traded miners absorbed a significant portion of this capacity, the saturation of the Texas grid (ERCOT) and rising industrial tariffs in the United States by late 2022 forced a second wave of migration. This “secondary capital flight” sought jurisdictions with three specific characteristics:

- Low Base-Load Energy Costs: Ideally below $0.04 per kWh to remain profitable post-halving.

- Regulatory Ambiguity: A willingness to trade energy for foreign currency without stringent KYC/AML choke points initially.

- Stranded Power Capacity: Markets with generation surpluses but transmission bottlenecks.

Africa, particularly the Eastern and Southern power pools, presented an optimal match. The continent possesses significant untapped renewable potential that suffers from the “paradox of plenty,” where generation capacity exists but cannot be monetized due to a lack of local industrial demand.

1.2 The 2024 Halving as an Accelerant

The Fourth Bitcoin Halving in April 2024 reduced the block subsidy from 6.25 BTC to 3.125 BTC. This programmatic monetary tightening decimated the margins of miners operating in high-cost jurisdictions. It acted as a powerful centrifugal force, spinning older, less efficient hardware out of North America and into the Global South.

Industry analysts noted that as margins compressed, the only survival mechanism for operators of mid-generation hardware was to seek “nearly free” power. Africa became the destination for this hardware lifecycle extension. Chinese firms, restricted at home and priced out of the US, began aggressively acquiring capacity in Ethiopia, creating a “secondary market” for exa-hashes that fueled the continent’s rapid statistical rise.

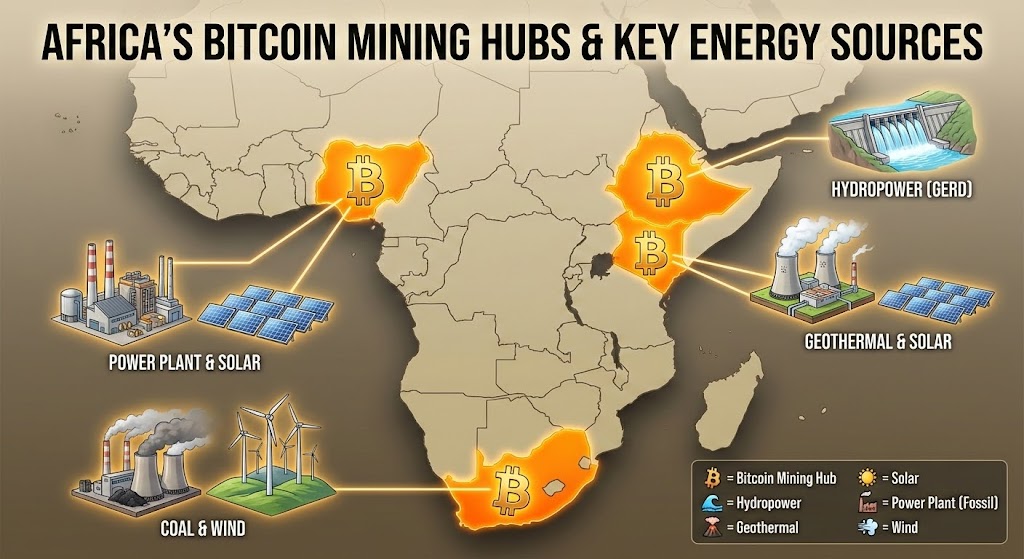

1.3 Continental Hashrate Distribution Overview

The distribution of mining activity across Africa is highly uneven, concentrating heavily where state-level energy surplus meets foreign capital interest.

- Ethiopia (The Industrial Model): Represents ~2.5% – 3.0% of global share. Driven by the GERD hydro project and foreign capital (China/Russia).

- Nigeria (The Resilience Model): Driven by local/diaspora capital using gas, hydro, and diesel to hedge against currency inflation.

- South Africa (The Grid Independence Model): Institutional and private miners leveraging solar to mitigate grid instability.

- Kenya (The Development Model): Focused on rural electrification and geothermal integration, regulated by the VASP Act.

Part II: The Ethiopian Hegemon – Anatomy of a Gold Rush

Ethiopia’s emergence as the singular heavyweight of African mining is the defining story of the 2021–2025 period. The nation’s contribution alone accounts for the vast majority of the continent’s hashrate growth, a development inextricable from its hydro-industrial ambitions.

2.1 The GERD and the Logic of Surplus

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile is the largest hydroelectric project in Africa. Its completion created a massive, immediate surplus of electricity. With domestic electrification rates still developing and transmission infrastructure delayed, Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP) faced a crisis of “stranded electrons”—energy that is generated but generates no revenue.

Bitcoin mining presented a plug-and-play solution. Unlike traditional factories, a mining container requires no complex supply chains—only a cable. In 2022, the government legalized “high-performance computing,” allowing miners to enter as energy consumers. EEP established a tariff of approximately $0.0314 per kWh, significantly lower than the global industrial average.

2.2 The Scale of Deployment

The response from global capital was immediate. By early 2024, EEP had signed agreements with 21 mining companies, predominantly foreign-owned. The scale of these operations dwarfed previous continental projects:

- West Data Group (Hong Kong): Committed $250 million to develop mining infrastructure.

- BitCluster (Russia): Constructed a 120 MW facility in Addis Ababa.

- BIT Mining (China/US): Acquired a 51 MW operational facility to deploy older machines no longer viable in the US.

By the end of 2024, the sector was consuming an estimated 600 MW of power. While EEP reported earning over $55 million in foreign currency in under a year, the rapid expansion brought unforeseen challenges.

2.3 The Grid Strain and Policy Reversal

The sheer velocity of this expansion exposed the fragility of the “Grid Stabilizer” narrative. While miners were intended to consume surplus power, their demand began to compete with other critical loads near Addis Ababa substations. In response, the Ethiopian government issued a directive halting new mining permits to manage load balancing. This marked the end of the “wild west” phase and the beginning of a constrained, regulated era.

Part III: The Economics of Hashrate Exfiltration

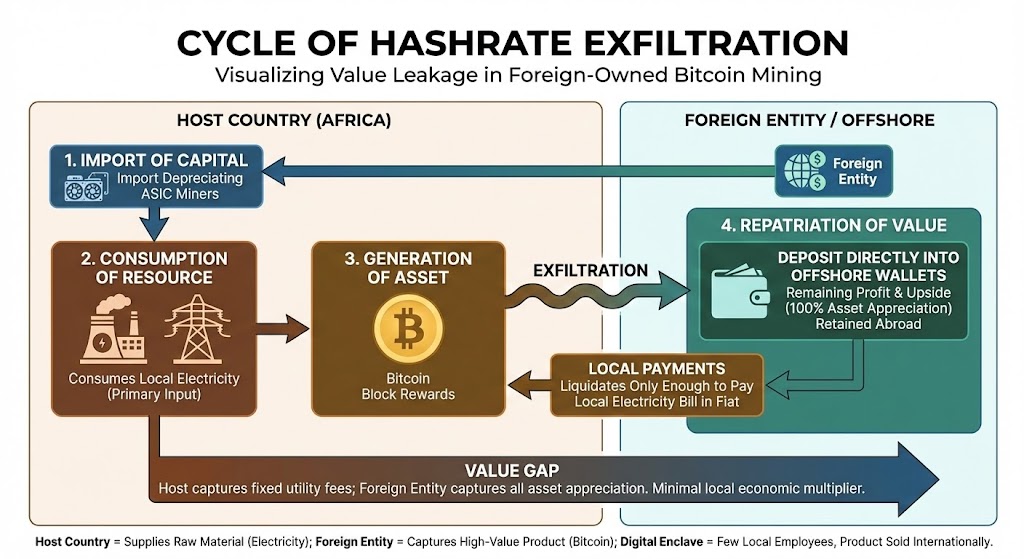

While the aggregate hashrate numbers are a technical success, the economic reality for African nations is ambiguous. We introduce the concept of “Hashrate Exfiltration” to describe the specific mode of value leakage occurring in this sector.

3.1 Defining the Mechanism

In traditional extractive industries, the host country captures value through royalties and labor. In foreign-owned Bitcoin mining, the mechanism of extraction is digital and frictionless. The cycle functions as follows:

- Import of Capital: Foreign entities import depreciating ASIC miners.

- Consumption of Resource: The entity consumes local electricity (the primary input).

- Generation of Asset: Bitcoin block rewards are deposited directly into offshore wallets.

- Repatriation of Value: The miner liquidates only enough Bitcoin to pay the local electricity bill in fiat. The remaining profit—the “upside”—is retained abroad.

For businesses looking to understand how to manage these cross-border flows efficiently, solutions like a USDT payment gateway can provide the necessary infrastructure for stablecoin settlement, ensuring better liquidity management.

3.2 The Value Gap

The disparity between the value captured by the host (utility fees) and the value captured by the miner (asset appreciation) is profound. EEP earns a fixed rate regardless of Bitcoin’s price performance. Meanwhile, the miner captures 100% of the asset appreciation. Critics argue this replicates colonial-era dynamics, where the host nation supplies raw material for a low fee while the foreign entity captures the high-value finished product.

3.3 Ownership Structures and “Digital Enclaves”

High capital barriers exclude most local entrepreneurs, resulting in “digital enclaves.” These facilities employ few locals and sell their product on international exchanges. The economic multiplier effect within the local economy is minimal. Furthermore, the presence of state-backed foreign actors seeking sanctions-resistant assets complicates the geopolitical picture for host nations.

Part IV: The “Gridless” Counter-Model and Community Value

Amidst the industrial giants, a distinct model has emerged in East Africa that challenges the exfiltration narrative. Pioneered by Gridless and the Green Africa Mining Alliance (GAMA), this approach focuses on decentralized, community-integrated mining.

4.1 The Anchor Tenant Thesis

Rural electrification faces a “initial demand” problem: new mini-grids often lack enough immediate consumption to be profitable. Gridless solves this by using Bitcoin mining as an “anchor tenant.” The miner buys all surplus power that the village does not use, guaranteeing revenue for the power producer and making the project bankable.

Using proprietary software, the system monitors grid frequency. When the village needs power, the miners automatically throttle down. When the village sleeps, the miners spin up. This smart curtailment ensures the community always has priority.

4.2 Evidence of Local Capture

Unlike the industrial model, this approach is designed for local value retention:

- Tariff Subsidies: Mining revenue allows Independent Power Producers (IPPs) to lower electricity prices for the community, sometimes by up to 30%.

- Expansion: In Zambia, this model financed connections for hundreds of families previously off-grid.

- Revenue Sharing: Agreements often ensure the energy provider participates in the Bitcoin upside.

For community projects looking to accept donations or payments to fund such infrastructure, integrating a crypto payment button can streamline the process of receiving support from global donors.

4.3 The GAMA Ecosystem

The Green Africa Mining Alliance (GAMA) includes members like Gridless, Trojan Mining (Nigeria), and QRB Labs (Ethiopia). This alliance lobbies for regulations that recognize mining as a tool for rural development rather than just a source of forex extraction.

Part V: Regulatory Architectures and the Path to Formalization

The regulatory environment across Africa has matured significantly between 2023 and 2025, moving from knee-jerk bans to sophisticated frameworks.

5.1 Kenya: The VASP Act 2025

Kenya has established itself as a regulatory leader with the Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASP) Act of 2025. Aiming to remove Kenya from financial “grey lists,” the Act creates a dual oversight regime involving the Central Bank and the Capital Markets Authority.

Miners must now be licensed entities with physical presence rules. This formalization allows miners to bank locally, reducing financial opacity. For businesses navigating these new compliance requirements, robust technical integration is key. Developers can refer to our API documentation for secure and compliant payment setups.

5.2 South Africa: Integrating Crypto into Finance

South Africa’s Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) has declared crypto assets as financial products. This has pushed the industry toward professionalization, with clear taxation guidelines. Due to grid instability, South African miners often operate “behind-the-meter” using solar arrays to ensure business continuity, effectively using mining to subsidize their energy independence.

5.3 Nigeria: The Grey Market Giant

Nigeria remains a complex jurisdiction. While banking bans have been lifted, mining occupies a regulatory grey zone. Operators often leverage “captive power” (private gas or hydro) to insulate themselves from the national grid, keeping them largely outside the formal regulatory net compared to their Kenyan counterparts.

Part VI: Environmental Realities and the Green Narrative

The narrative that African mining is “100% green” is a powerful marketing tool, but the reality requires nuance.

6.1 The Hydro Dominance

It is empirically true that the majority of new hashrate in Ethiopia, Zambia, and Malawi is hydro-powered. Ethiopia’s renewable grid means the carbon intensity of mining there is negligible compared to coal-heavy regions. However, environmental impact extends beyond carbon.

6.2 Water and Land Footprint

In water-stressed regions, the diversion of hydro resources raises ethical questions. Future droughts could create conflict between agricultural needs and mining operations. The “consumptive use” of water via evaporation in hydro reservoirs is a metric that regulators must begin to track more rigorously.

6.3 The Gas Flare Opportunity

In Nigeria, mining offers a solution to methane mitigation. By deploying mobile containers to oil wellheads, companies can combust flared gas to power miners. This converts potent methane into less harmful CO2 and useful work, representing a significant potential for “carbon-negative” mining.

Part VII: Future Scenarios and Strategic Recommendations

The 2021–2025 period was the “installation phase” of African Bitcoin mining. The next five years will be the “deployment phase,” where the economic logic is tested.

7.1 Scenario A: The Sovereign Stack (High Optimism)

In this scenario, African central banks recognize Bitcoin as a strategic reserve asset. Countries mandate that a percentage of mined Bitcoin be sold to the Central Bank, building a “Sovereign Bitcoin Fund.” The Gridless model becomes the standard for rural electrification projects, unlocking gigawatts of micro-hydro potential.

7.2 Scenario B: The Utility Death Spiral (Pessimism)

Unchecked industrial mining destabilizes grids, leading to political backlash and bans. Foreign capital flees, leaving behind stranded assets. “Exfiltration” continues in grey zones with no tax revenue accruing to the state, leaving Africa as a passive host.

7.3 Strategic Recommendations for Policy Makers

To achieve the optimistic scenario, policymakers must pivot from passive hosting to active integration:

- Tax at Source, Hold in Asset: Utilities should consider accepting a portion of payments in hashrate or Bitcoin.

- Local Ownership Mandates: Licensing should require Joint Ventures to ensure technology transfer.

- Grid Integration Standards: Mandate automated curtailment software for all industrial miners.

- Digital Free Trade Zones: Establish zones where hardware imports are duty-free in exchange for financial transparency. Businesses operating here can utilize a crypto e-commerce platform to manage international trade flows efficiently.

Conclusion

The rise of Africa’s Bitcoin mining sector to 4% of global hashrate is a testament to the continent’s energy potential. However, hashrate is a vanity metric; value capture is the reality. The current dynamic of Hashrate Exfiltration threatens to turn this digital renaissance into a resource curse. The path forward lies in the Gridless model of community integration and a robust regulatory framework that asserts sovereign ownership over digital commodities.

For merchants and enterprises looking to participate in this evolving digital economy, whether through crypto invoicing solutions for B2B settlements or accepting payments via Ethereum (ETH), the infrastructure is ready to support the next phase of Africa’s financial sovereignty.

External References: